When I was coming up as an organist, I complained to a friend once about some goings on in a meeting of the local chapter of the American Guild of Organists. He replied with the classic joke, “Well, you know, the AGO is really just an organization for little old ladies of both sexes.” It’s a pretty good joke as jokes go. I didn’t quite realize how “classic” it was.

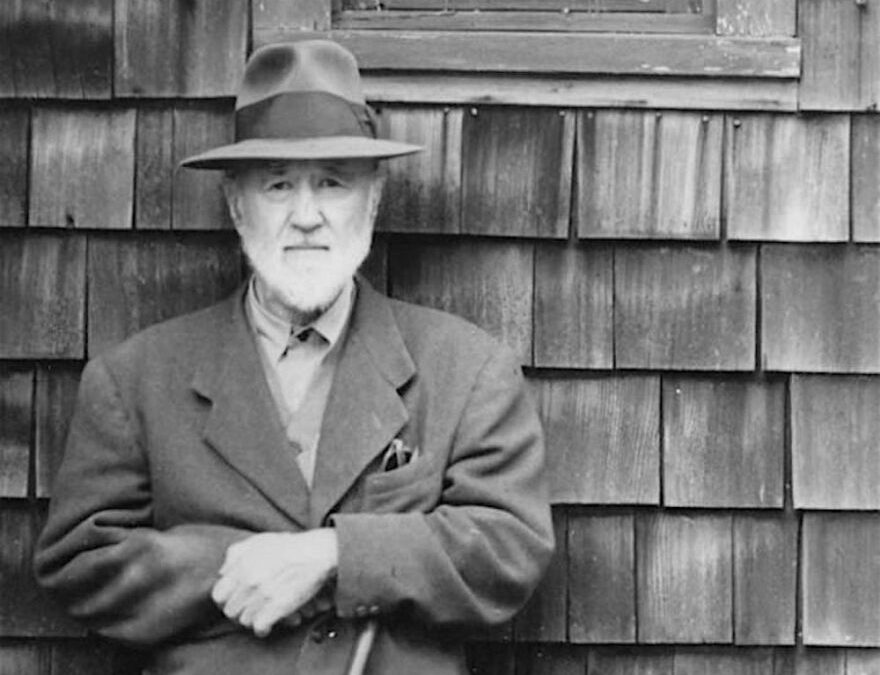

In my regular spelunking trips through the annals of St. Taruskin, I discovered that the old chestnut had a darker history. It was Charles Ives that regularly berated “old ladies of both sexes” to attack what he saw as the “effeminate” in music. His Second String Quartet was written to “have some fun with making those men fiddlers get up and do something like men.” This thing even has the marking, “Andante emasculata.”

It’s hard to know what any of this means anymore. It naturally brings to mind Wagner’s “Das Judenthum in der Musik.” On the one hand, we all experience the tropes of a particular musical culture and can easily recognize them when they are cited. We don’t really want to de-culturize a sound or a musical scale in such a way that exhausts the richness of the culture that provided it to the world. We also don’t really want to silo it in such a way that suggests that it is so provincial that it cannot communicate outside of its nascent space. In other terms, when it comes to culture, the “melting pot” is a bad analogy. We want a good stew where we can have potatoes and onions that retain their distinctive characteristics while joining together to make a good meal.

Wagner’s “Judenthum” was not really about musical things. It was about his own petty and insecure jealousies. In the same way, it is hard to figure out something other than the sinister lurking behind Ives’s complaints about the feminine in music. So we get all the speculation about Ives’s own sexual insecurity. That question is rather uninteresting to me. What is interesting is the hard questions about gender.

I was a kid of the 70s and 80s, and I was raised on a steady diet of Kierkegaard when I came of age. “If you label me, you negate me” and all that. So for me, being a boy that played piano in a sensitive fashion could be perceived as “feminine.” And our generation spent a lot of time saying things like, “There isn’t anything effeminate about being sensitive any more than suggesting that to be a strong, powerful leader is masculine. Women can be bosses and men can be sensitive.”

The hard part now, is that the younger generation has leaned into a lot of the stereotypes that my generation sought to tear down. I’m not sure of the solution to how to think about the problem. One way of course, is to go with the younger generation and celebrate the “eternal feminine” in things. “Ives’s be damned, we going to be men that play like women.” That seems rather silly, and in the same way that we like to silo culture, we are making gender into something that can’t communicate outside of itself.

The other way is to obliterate all distinctions. We are humans that play like humans. There is something right about that, but it doesn’t seem to respect the authentic nature of cultural distinctions. I don’t know what the Via Media is here, but it’s what I’m looking for. I want the good stew where the potatoes and onions don’t get amalgamated in in a melting pot.

Sarah Coakley’s thoughts on the gender-bending nature of priests is interesting here. It preserves the distinctions and lets individuals flow back and forth while maintaining the categories. The other option is to do like Berdyaev did and suggest that Jesus was an androgynous figure that was the ultimate model we are all aiming toward. There, you blow up the distinctions altogether. His thought makes the aim that we all turn out to be “little old ladies of both sexes” in a Platonic sense, and maybe that’s the best place to wind up.

Recent Comments