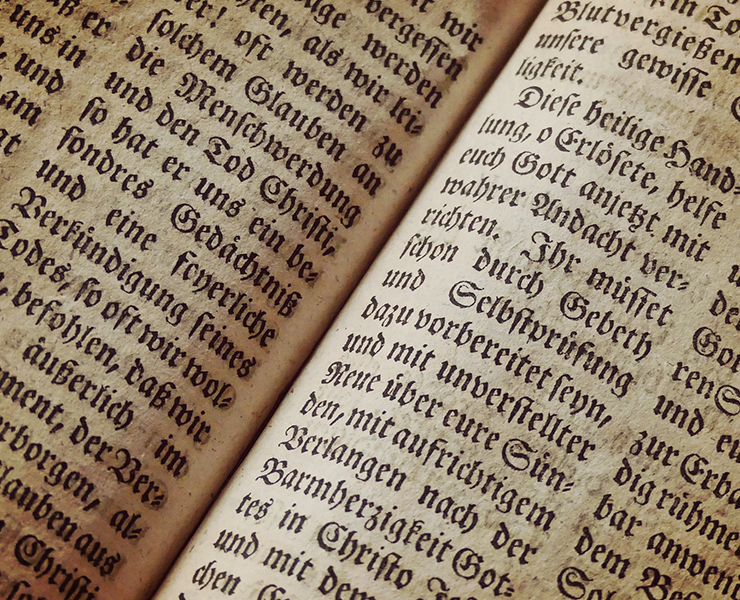

The term “fundamentalist” originates from that indefatigable wellspring of tuckermanity: the Presbyterian. A business tycoon in the 1920s became concerned about the Princeton theological faculty and their affinity for recent German Biblical scholarship. Deciding the academics were too “liberal,” he financed an attack on them. The attack advocated a return to the “fundmentals” of the faith in a series of tracts. Chief among these fundamentals was the idea that the Bible is inerrant and should be read literally whenever possible. Of course, this approach to reading the Bible is neither ancient or original. In fact, they would have been wholly unrecognizable to most Christian from the first fifteen to sixteen centuries of the faith. They took an idea that was really fully formed in the 19th century, claimed it was “original,” and attacked anyone that opposed them as introducing new material into the faith. We use the term “fundamentalist” now for any group that rejects modern scholarship for a more supposedly originalist position. Wherever fundamentalism occurs, we see the same pattern. A group rejects a modern idea and advocates for a return to a more pure position. The “original” position they advocate for is inevitably not original at all, but a different modern idea.

There are fundamentalists in every line of work that involves hermeneutics. Justice Alito regularly produces some obscure, antiquarian reference to justify his opinion. Presumably, he’s does it to make sure that his dance card is full at the annual strict constructionist ball. In music, we have our fundamentalists too.

It seems redundant to rehearse this history here, but apparently, not enough people have taken my Baroque Performance Practice class. In brief, the HIP [Historically Informed Performance] movement (don’t let the name fool you because they are anything but) started when folks like Christopher Hogwood et alia were being rebellious in the 1970s. They were trying to play Baroque music in a way that wasn’t informed by the 19th century. So, they dug their crumhorns and sackbuts out from the back of their closets. They put new reeds into their oboe da caccias, d’amore, and hotboys (oh boy!) They turned their tuners down to 415Hz, and started reading old treatises about how to play. Keyboard players who had long been enjoying the evolutionary advantages of opposable thumbs started learning how to play scales with only two fingers. Why? Well, at least according to his son, before J.S. Bach came along, keyboards were played almost exclusively with the fingers and not with thumbs, and one day, old man Bach looked down to the end of his arms and saw those thumbs sticking out like a sore…well you get the idea. He said, “Hey, what are these things?! Maybe I could use them when I play!” The keyboard players in the 1970s started thinking it was a good idea to imitate the way keyboards were played before Bach and started pawing around the keys without the opposable digit. Scales were played using fingerings like 2 -3 – 2 -3 – 2 – 3 – 2 – 3. C.P.E. Bach says something like, “Before my father, we never had enough fingers to play, and now we have too many.”

It was all in good fun, and no one was getting hurt except for four singers. The most sadistic of the new wave of HIP performer/scholars was Joshua Rifkin. In his quest to follow Bach’s “original” practices (or at least what some of the evidence suggests was the practice), he did a Bach b minor Mass with only four singers! I think those four singers must have been suffering from some sort of Stockholm syndrome to subject themselves to that kind of punishment. Other than those four singers though, no one was harmed in the making of the product, and they were coming up with some cool and innovative approaches to early music performance. Everything was going along swimmingly until someone dropped the “A-bomb.” One of the HIPsters said they were performing the early music “authentically.” Instead of a 19th century style of performance being imposed on a 17th century style of composition, they were pulling the gloss off the palimpsest and revealing the original. They were doing the music the “correct” way. The were doing the music the way it was done back when it was written — well, mostly. I mean, they weren’t using performers filled with gout and cholera and consumption and wearing wigs and stuff, but other than that, they were doing it just the way it was done back then…also, without syphilis, but other than that, just like it was back then.

It was at that point that musicologist and world-class, irascible curmudgeon Richard Taruskin picked up his lance, mounted his Rocinante, and started tilting. He went after these HIPpies in a very public way. He didn’t necessarily mind what they were doing (in fact, he rather liked much of it), but he didn’t think what they were doing was necessarily “the way they did it back then.” What they were doing was re-interpreting the music for modern times just like the musicians did in the 19th century. He went on to systematically show that their interpretations were more influenced by Stravinsky’s aesthetic than by any supposed fidelity to Baroque treatises. In any case, non of it was a more “authentic” approach to the text. It was a modern approach to something old, and all those 19th century style recordings with “Furtwängler’s unforgettably ham-fisted continuo chords, banged out at full Bechstein blast with left hand coll’ottava” aren’t somehow “inauthentic.” Furtwängler was doing the same thing as the HIP performers. Re-interpreting the music for his time. He was just using a 19th century aesthetic to do it, and the HIPpies were using a 20th century aesthetic.

In the end, the HIP performer/scholars backed down. The sails of their windmills in tatters, they came out with public statements like this one from Christopher Hogwood. Hogwood et alia had been saying that what they were doing was akin to a fine art restorer. Hogwood claimed they were scraping the dirt off the painting to reveal the original work. After Taruskin had rather publicly shown that what they were doing was precisely not that but imposing a modern spin on the original, an interviewer asked him about it, and Hogwood responded with this gem:

“a lot of what one says to try and make the topic acceptable, explicable and attractive to the average consumer will not stand up to logical scrutiny, but it was never meant to.”

Thanks, Sir Christopher. That’s some proper claptrap. In other words, “Well, when we said ‘authentic’ we didn’t really mean ‘authentic.’ We were just trying to sell some records.”

So why re-tell a well known story here? Because for the last thirty years, I’ve been playing for conducting classes at Universities of all sizes in multiple states. These conducting classes are always “conducted” as if this story never happened. Despite Taruskin showing that the aesthetic being used for conducting early music is more based in Stravinsky’s aesthetic than Baroque treatises, and despite Sir Christopher backing down from his earlier claims, conducting students are taught to conduct things in this modernist style that purports to be older than it is. It’s a naive musical fundamentalism that gets passed down from teacher to student all across the country. I’m going to mount my own Rocinante and do some tilting at musical fundamentalism in this set of four essays. All Sancho Panzas are invited to join.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks