If we think about the British Museum displaying a vase from ancient Babylon, the concept of “cultural appropriation is clear. They likely picked up the vase during the glory days of the Empire. In that case, one group takes something from another group. Stealing is wrong. So, one culture appropriates something from another culture. However, if we think about how an F# gets lifted from one group and used in another context, the problem gets quite a bit knottier.

In some cases, it’s not all that hard to untangle. Young music students learn that the tritone is the “devil in music,” but Pat Boone is a much stronger contender for the moniker. He deliberately mined songs written by black artists, recorded them, and put them out to compete with the artist’s own version. When we combine it with his petulant politics and the offensive statements he’s written (which are at best racially tone-deaf and at worst blatantly bigoted), he’s an easy target for a case of cultural appropriation in music. I think the actual historical record is slightly more complex than that, but I’m suggesting that we could make a cogent argument that Boone was culturally appropriating music of others for his own profit at the expense of others.

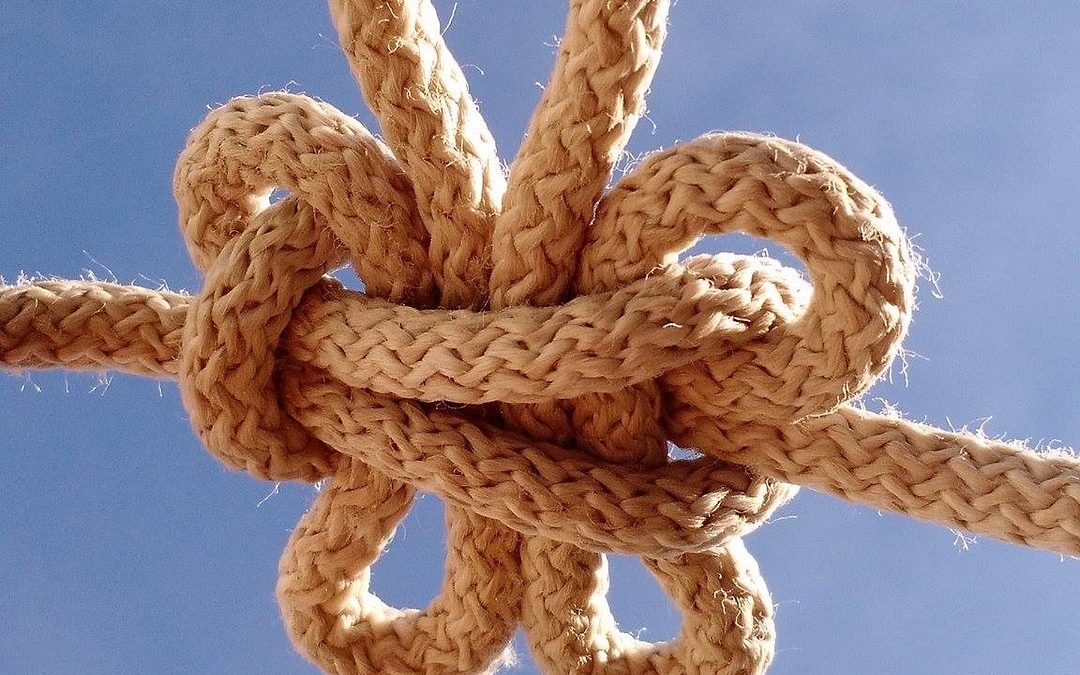

The question of cultural appropriation gets harder if we think about Paul Simon’s Graceland. That album was rightly celebrated for its use and borrowing of South African music. Specifically, recordings of mbaqanga music originally inspired Simon to write it. Of course, mbaqanga was originally developed by combining Zulu music with forms of American popular music, so the South Africans were doing a bit of borrowing of their own. But then again, the borrowed American popular music they used in South Africa came from American musicians borrowing from African music. It was the music brought over by slaves which was combined with a variety of European influences and American church music. To be fair, much of the music that the slaves were singing was not actually the same music they sang in Africa. It was a new music that was developed by taking the African music that they knew and combining it with the new music they were hearing in America. But, it’s not like the music that the West Africans were making before they were enslaved sprang fully formed from the head of Zeus like some pristine Athena. Musicologists now argue that the West African music that the slaves brought with them was a combination of indigenous music and music borrowed from Sufi Muslims. That music evolved via American slavery to the development of the Delta Blues (and then to American popular forms). It turns out that one of the major influencing factors on American popular music was Islamic musical practice and form. The point here is that whenever we try to put our finger down on a culture and say, “Here is the spot where it is,” we find that it is just a confluence of previously amalgamated influences. We are, of course, putting our finger down on unique musics. The difficulty is trying to untangle the Gordian knot of cultural influences that contribute to form it.

I suppose if we chased the genealogy down far enough, we might come to some pristine Adam and Eve of an ‘F#’ in some musical Eden on the banks of the Euphrates. We could then sit down by the river and listen to the unadulterated paeans and dithyrambs in a Bacchanalian ecstasy. After we wiped a tear or two from our eyes, it would come time to pay the bill, and even assuming a good APR rate, we would find that when it came time to pay back all these loans, the ‘F#s’ would have all appreciated into ‘Gs’ or even ‘As’ at the least.

Again, this isn’t to suggest that the places we put our fingers down aren’t unique and valid works of art just because they have a genealogy. West African music isn’t any less West African or less valuable because it is influenced by Sufi music from the Arab world. It becomes, ipso facto, unique by the way various influences are combined. Just because we can descry influences does not mean that we are somehow exhaustively explaining a thing. Taking something apart the way you would disassemble a car engine might explain certain systems on a lower level. Once all the contributing features are explained, we might have a better understanding of how an engine works. But, art is not an engine. Unraveling the strings that tie it together only shows other things that can’t be explained, and we are left talking about something other than the actual piece of art. Art tends to be stubborn that way. Giving an autopsy to the ontic whole only leaves us with puzzle pieces that can’t be reassembled. Deconstructing something isn’t a guarantor of epistemological certainty.

Maybe thinking of music in terms of cultural “ownership” isn’t the best framework for a starting place. I know that consumer capitalism wants to turn everything into a product that can be assigned a monetary value and a proprietor, but it is possible that some things might float above all of that in the spiritual ether that connects all of us together as humanity. Musical language might develop in such a way that we all combine our influences into unique little pidgins that are too personal and complex to unravel genealogically. Even if we could, it would do little to explain anything in an etiological sense. The influence of American jazz and Indonesian gamelan music on Debussy is not determinative in a pathological way. He didn’t get “infected” with something that had a necessary result. Debussy was among many musicians who heard those musics. All of them developed their own harmonic reactions to it. While we might be able to point to a chord here or there and say, “Here is the jazz influence,” it can’t be parsed out (as some have suggested) in such a way that you could determine the “percentage” of jazz influence for purposes of financial compensation. This isn’t to suggest that all cultural exchanges happen on an equal playing field. I don’t believe they do. It’s just that there is no way to suss out the contributing factors in a quantifiable fashion any more than you could dissect your personality and make a pie chart of the influence of various parents, grandparents, friends, mentors, teachers, trees, pets, novels, and DNA.

So, the first problem in addressing cultural appropriation is figuring out where to draw lines around a thing and figure out who it belongs to. Easy with a vase. Not so easy with a rhythm or an F#. Or maybe we should say, “easier” with a vase. Pottery has its own history and genealogy. It’s just easier to conceptualize the idea of appropriation when it is one of the plastic arts. We can understand a physical object that is taken from one person and placed somewhere else. Invisible things like music are much harder to assign an owner.

To read the second essay in this series, click here: https://kurtknecht.com/cultural-appropriation-in-music-meditation-2-knowlege/

To read the third essay in this series, click here: https://kurtknecht.com/cultural-appropriation-in-music-meditation-3-influences/

Recent Comments